Unraveling the Mysteries of Chicago and Texas Blues Shuffles, Part 1

Born from the boogie-woogie sounds of jazz piano in the very early 20th century, the swinging shuffle groove is built from an insistent and repetitive forward-leaning rhythm that is generally written in 12/8 meter—wherein four consecutive beats are each subdivided into three evenly spaced eighth notes—and comprises a repeating quarter-note/eighth-note rhythm that sounds like “da—da, da—da, da—da, da—da.”

There may be no more an enduring sound that has spanned the long, diverse history of popular music than the blues shuffle.

Born from the boogie-woogie sounds of jazz piano in the very early 20th century, the swinging shuffle groove is built from an insistent and repetitive forward-leaning rhythm that is generally written in 12/8 meter—wherein four consecutive beats are each subdivided into three evenly spaced eighth notes—and comprises a repeating quarter-note/eighth-note rhythm that sounds like “da—da, da—da, da—da, da—da.”

In this edition of In Deep, we’ll unravel the guitar artistry of three masters of the blues shuffle: Chicago’s Jimmy Reed and Muddy Waters, and Texas’ Lightnin’ Hopkins. The first blues boogie/shuffle to become popular was “Pine Top’s Boogie,” released in 1929 by pianist Pine Top Smith.

By the mid Thirties, the boogie rhythm had been adapted to many different styles of music, including the swinging big-band jazz of Benny Goodman, the jump blues of Louis Jordan, hillbilly music and country-and-western swing. But the shuffle rhythm also has origins in the late Twenties recordings of such seminal Delta blues figures as Charlie Patton, Willie Brown and Tommy Johnson.

Delta blues pioneer Robert Johnson recorded the classic blues shuffles “Dust My Broom” and “Sweet Home Chicago” in 1936, and shortly thereafter, essential artists such as Son House, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Elmore James, John Lee Hooker and Lightnin’ Hopkins developed blues music, and the intricacies of the shuffle rhythm, to a fine art form.

Let’s begin with the great Chicago bluesman Jimmy Reed, who penned blues shuffle classics like “Ain’t That Lovin’ You Baby,” “You Don’t Have to Go,” “Bright Lights, Big City,” “Baby What You Want Me to Do” and many others.

To say that Reed’s songs have been influential would be a huge understatement. It’s impossible to imagine the blues guitar lexicon without his influential playing style and well-loved, oft-covered songs. Reed often performed with guitarist Eddie Taylor, and the manner in which they played complementary chordal and single-note melodic parts together laid the groundwork for the two-guitar approach later expounded upon in the blues rock of the Yardbirds’ Chris Dreja and Eric Clapton (and, later, Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page), and the Rolling Stones’ Keith Richards and Brian Jones (or Jones’ successors Mick Taylor or Ron Wood).

Richards refers to the intertwined sound of the complementary guitars in the Rolling Stones music as, “the fine art of weaving.” Employing a thumb pick and his bare fingers, Reed would use his thumb to lay down driving rhythms on the lower strings while fingerpicking melodic lines on the higher strings.

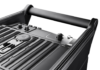

FIGURE 1 illustrates a rhythm part along the lines of “Baby, What You Want Me to Do,” played in the key of E.

The pickup bar features a rolling double hammer-on on the D string, followed on beat one of bar 1 with an open low E and a trill on the G string to the major third, G#, played simultaneously. Both the trill lick and the rolling double hammer on provide complementary melodic content to the insistent rhythm sounded on the lower strings.

In bar 9, B7/A is played by combining B7-type lines with the open A string, yielding an unusual, and signature, effect. Bars 11 and 12 serve as the “turnaround,” with single-note phrases based on the E blue scale (E G A Bb B D) setting up the “V” (five) chord, B7.

FIGURE 2 is based on another Reed hit, “You Don’t Have to Go,” which sounds in the key of F. Reed would move the capo up and down the neck to change keys, which enabled him to play all of his songs in the same manner—as if he were playing in the key of E without a capo (for example, “Bright Lights, Big City” is played with the capo at the fifth fret, sounding in the key of A).

Akin to FIGURE 1, a repeated melodic pattern is established on the higher strings, alternating against the driving rhythm part on the lower strings. Again, B7/A is used in bar 9, and the turnaround lick in bars 11 and 12 offers a slight twist, setting up a return to the initial lick from bar 1. A complete exploration of Reed’s music is required listening for any aspiring blues guitarist.

Also check out the great tribute album, On the Jimmy Reed Highway, recorded by legendary Austin, Texas, guitarists Jimmie Vaughan and Omar Kent Dykes in 2011. Texas blues master Lightnin’ Hopkins was a virtuoso guitarist who often performed solo, developing a chord-melody style that greatly influenced blues-rock icons Jimi Hendrix, Johnny Winter, Billy Gibbons and Stevie Ray Vaughan. Like Reed, Hopkins combined fingerpicking with the use of a thumb pick.

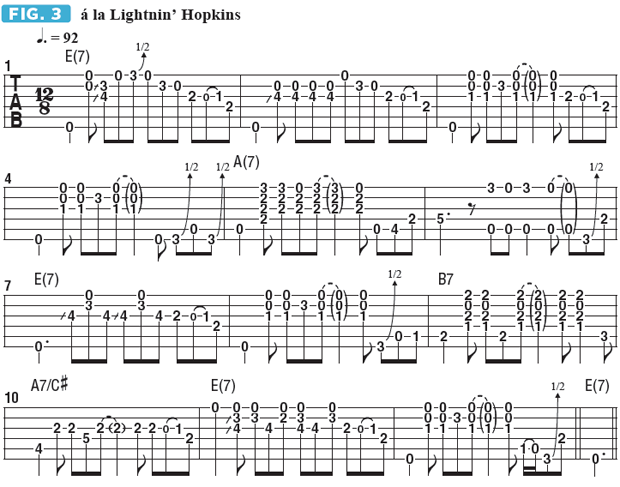

FIGURE 3 is played in the style of his song “Katie Mae,” and throughout, intricate melodic lines on the top three strings dominate the solo guitar performance. To execute these parts, alternate between the thumb and either the index or middle finger (or both used simultaneously). At bar 5, the “IV” (four) chord, A7, includes a simple melodic pattern on the high E string, moving between G at the third fret and the open string.

These single note lines are also based on the E blues scale. Muddy Waters, known as the “Father of Chicago Blues,” learned much of his guitar style from listening to Son House and Robert Johnson. He also fingerpicked with a thumb pick, and his initial solo recordings, such as “Feel Like Going Home” and “Rollin’ Stone,” became hits.

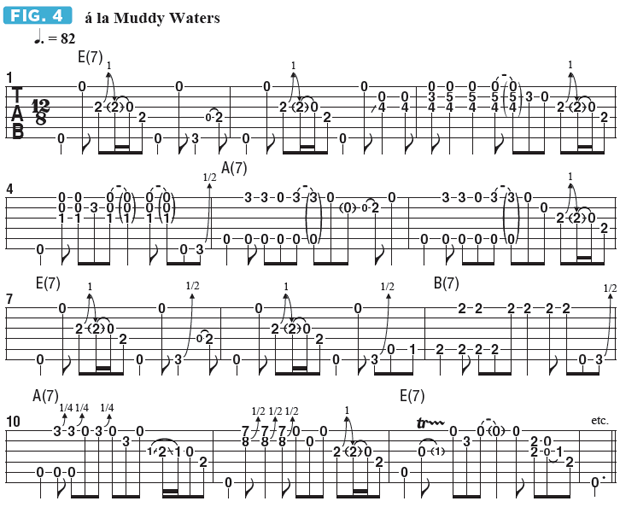

FIGURE 4, played in the style of “Rollin’ Stone,” features a consistently alternating low-string/high-string figure, adapted later by Hendrix as the basis for “Voodoo Chile (Slight Return).” Of the four parts illustrated, this is the most complex, so work through each bar slowly and carefully, striving for rhythmic precision and clean articulation.

Source: www.guitarworld.com