Ritchie Blackmore: Talking Tone, Gear, Deep Purple Years and a Rocking Rainbow Revival

Ritchie Blackmore’s stately residence has a view of the Long Island Sound and all the comforts of home—including a medieval dungeon.

“It’s a kind of studio-cum-bar,” he says. “Actually, it’s more of a bar, although I do all the records down there. It’s done up like a medieval dungeon. And when our producer, Pat Regan, flies in from California to do some production, we chain him to the equipment.”

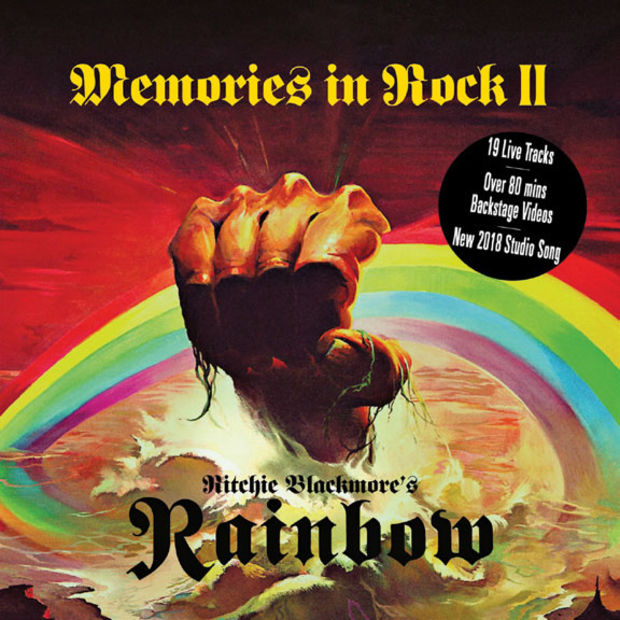

This strange sanctuary was also the site of rehearsals for Blackmore’s newest project, the live retrospective set Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow: Memories in Rock II. Over the space of two CDs and a DVD, Blackmore and the most recent Rainbow lineup blaze through stadium-razing performances of classics from Blackmore’s years with both Deep Purple and Rainbow. On track after track, Blackmore’s legendary legato phrases and beefy tonal nuances reaffirm his status as one of the great architects of metal guitar. Which is pretty good for a 71-year-old who has certainly lived through his share of wild years.

The band Rainbow was named after the legendary rock and roll bar and grill on the Sunset Strip in L.A., where Blackmore was living in the Seventies when he formed the group. “I used to live right behind the ‘Riot House,’ ” he recalls, alluding to the infamous Continental Hyatt House hotel on Sunset—the setting for many epic scenes of rock star debauchery. “When the Rainbow would close at three in the morning, John Bonham would come over to my place to carry on drinking.”

Blackmore has outlived many of his hard-living classic rock contemporaries. Over the course of numerous Deep Purple and Rainbow lineups, he has worked—and frequently fought—with many of metal’s top singers and sidemen, including Ian Gillan, Ronnie James Dio and David Coverdale. Active in rock ever since the Swingin’ Sixties, Blackmore has acquired a reputation as an irascible, volatile and demanding bandleader. But he’s full of praise for the new Rainbow lineup, which centers around 36-year-old, Chilean-born vocalist Ronnie Romero, a stalwart metal belter in the Dio mode.

Romero was discovered on YouTube by Blackmore’s wife, the singer and multi-instrumentalist Candice Night, who fronts the couple’s Renaissance-inspired side band, Blackmore’s Night, also serving as a Rainbow backing vocalist. She suggested that Ritchie get in touch with the young singer.

“Ronnie came out to see us where we were staying, in a castle in Germany,” Blackmore narrates. “I had my acoustic guitar, we just ran thorough a couple of Rainbow songs and he passed with flying colors. He’s a very nice guy, and I thought, You know, it might be interesting to do a few shows, just for old time’s sake. Basically nostalgia. That’s how it all started.”

The rest of the lineup is comprised of musicians who have worked with Blackmore’s Night in the past—bassist Bob Nouveau, drummer Dave Keith, keyboard player Jens Johansson and backing vocalist Lady Lynn. The music on Memories in Rock II was culled from live performances by the group in the U.K. in 2017. The DVD included in the set contains interviews and backstage footage, offering a complete chronicle of this latest chapter in Blackmore and Rainbow’s history.

Revisiting musical highlights of his long and storied career seems to have put Blackmore in a mellow and reflective mood. When Guitar World spoke to him from his home on Long Island, he was affable, generous and eager to share stories from his many years in rock.

How do you rate this new incarnation of Rainbow, as compared with previous lineups?

I like it, because I think it’s more musical. With Ronnie James Dio, in the beginning of Rainbow, everything was fine. He was a great singer. But he didn’t have a lot of patience. So we kind of got on each other’s nerves after two or three years. Which means we weren’t really creating any longer at that point. And with [drummer] Cozy Powell, he was a pretty uptight guy too. And I’m quite domineering. I like to steer the bus. So after a few years, we were arguing too much and weren’t as creative. That’s when the first lineup folded. Following that, I wanted to be more accessible and on the radio. So that’s when we started recording stuff like the ballads I wrote with Joe Lynn Turner. He had more of a commercial voice.

I think this new incarnation also has the capability of being quite commercial, if we want to be, with Ronnie Romero’s voice. But at the same time, we can try all the good songs that Rainbow has done in the past. At the moment I’m not looking at this lineup as a recording vehicle—just going out and having fun playing all the old songs to the fans who would normally not hear it.

What traits or qualities to do you look for in musicians to work with?

Somebody who likes to drink is obviously important. [laughs] You can make a joke of it, but I’ve met people who say, “I don’t drink at all. I stopped drinking five years ago.” And those people I’ve always had problems with. They might not drink, but they do everything else that’s crazy. If someone says, “I don’t drink much; I just like to have a few,” that’s fine. But it’s when they make that big statement that I say, “Oh dear, then, what’s your real problem? I might be dealing with the wrong person here.”

Of course, there are other things I look for as well. In a bass player, rhythm is very important. Is he tight with the drums? I don’t like a flashy bass player that runs across the stage waving to the audience half the time. And I’m thinking of one particular person who does that. He’s quite famous actually.

Can we say who?

You know, I actually can’t remember. What was the name of that band? It was back in the Eighties, Nineties. It wasn’t Foreigner, but something like that.

at London’s O2 Arena on June 17, 2017—(from left) Jens Johansson, Bob Nouveau, Dave Keith, Blackmore and Ronnie Romero

The songs on Memories in Rock II seem to represent the whole broad sweep of your career. Not only Rainbow but Deep Purple as well. Is it a challenge to find new life in something like “Smoke on the Water,” a song that you must have played thousands of times?

That one’s easy, in a way, because you can improvise so easily on the chords. And the rhythm is just very kind of flowing. And I think everyone wants to hear “Smoke on the Water,” although when we did it onstage, we didn’t get the reaction from the crowd that I thought we would. There were a few comments that, “Deep Purple does that. Why bother?”

I thought it was cool and interesting that you started with the verse, rather than the big riff.

Well, we’ve played it so many times, you have to find different ways to do it. Just starting with the guitar riff, as it was originally written, can be a bit mundane. But, yeah, I do prefer playing it with the verse first and coming in with the impact of the riff later.

Because then the chorus hits first, and that’s just as iconic as the riff.

That’s right. Although it’s funny, because sometimes people in the audience don’t know what we’re playing when we start out with the verse. But I never get tired of playing “Smoke on the Water.” Surprisingly enough, I don’t hate it. I was talking to Ian Anderson, and I said, “Are there any songs you hate playing?” He said, “ ‘Aqualung.’ Because we have to play it every show.” But I haven’t gotten to that stage yet. Maybe because I haven’t played “Smoke on the Water” probably in 20 years, because I’ve been focused on Blackmore’s Night. I mean I’ve played it off and on. But I haven’t been in a band that’s playing it every night on tour.

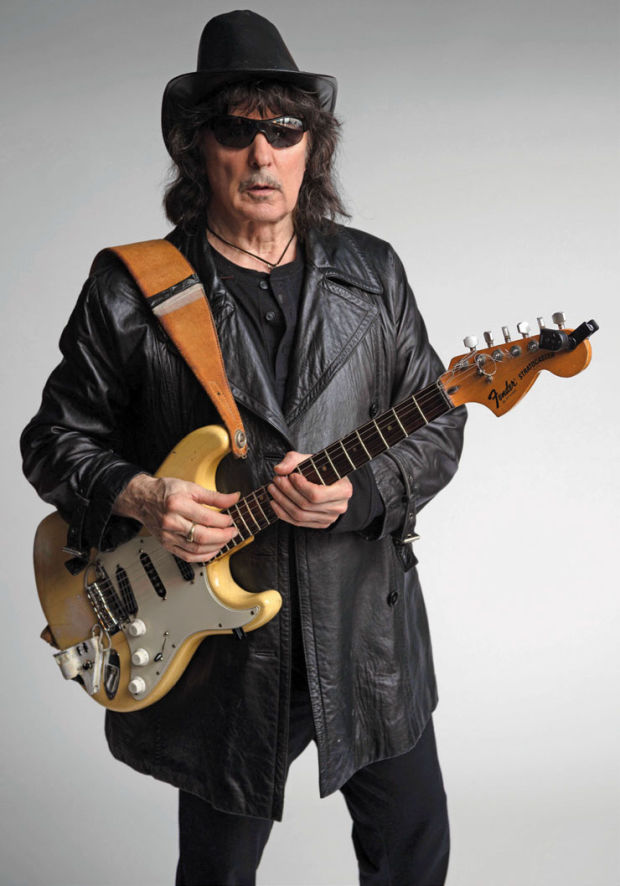

You’ve been playing Stratocasters for the better part of six decades now. But what prompted your initial decision to abandon the Gibson 335 you were playing in the early days of Deep Purple and take up the Strat?

I liked the way Hendrix’s Strat looked. A Strat has got that rock kind of look. So the visual thing attracted me first, even though it was an upside-down Strat in Hendrix’s case. I thought, I must try one of those some day.” I knew Eric Clapton’s roadie. He was a friend of ours. And I think Eric had given him one of his Strats as a present. Probably because Eric didn’t want it. I think it had a slightly bowed neck, which was making the action pretty high. [The roadie] said, “I’ll sell it to you for £60.” I bought it from him and I think I used it with a wah wah pedal on Deep Purple’s [1969 single] “Emmaretta.” So Eric Clapton’s throw-away Strat came in handy for me.

And when did you start scalloping the fingerboards on your Strats?

That was probably around 1969 or ’70. But I suppose it started back in ’66. I used to play an old classical guitar with a fretboard that was very pitted. And I loved the effect. It suited my fingers; it made sense. And the Strat seemed a little too glossy to me when I first got it. Probably it was because the Fender had thinner frets than Gibsons. So when I would slur a note, I found my finger kind of slipping off the string. So I thought, If I make the fingerboard more concave, I can grip it more. I didn’t know of anybody else who was doing it before I did. I didn’t think anybody else was that stupid—to spend three days sandpapering a guitar.

So with the scalloped fingerboard and some of your stylistic influences, can we make a case for your being the godfather of the Yngwie Malmsteen neoclassical thing? Do you feel a kinship, or a responsibility, there?

I know him and he’s a very nice guy. Excellent guitar player. A lot of people have kind of questioned his angle, but he obviously knows his stuff. He might be a bit too tall, but that’s my only criticism. I did meet his mother in Sweden, a very nice woman who reminded me of my mother back in England. So Yngwie and I get on fine. He’s like a family member. I definitely think he’s probably the best at what he does and—for what it’s worth—the fastest. And he doesn’t play the typical blues, minor kind of interpretations. He knows his scales. It’s more interesting.

That’s a trail you blazed as well—getting away from blues-based playing in rock.

I suppose that’s so. When I was 15 I saw a band called Nero and the Gladiators. They would dress up as Roman centurions. This was when every band had to have a uniform of some sort, whether it was red satin jackets or what have you. But this band dressed up as gladiators. They’d come onstage and I was so impressed that they’d play all these classical pieces, like “In the Hall of the Mountain King” by Edvard Grieg. This band did everything that was classical, but rocked it up. I said, “Wow, this is not just your Chuck Berry rock and roll band.” That really started me going in that classical direction, along the lines of playing a solo with very fast triplets like on “Highway Star” from [Deep Purple’s] Machine Head. That kind of sound really came from Nero and the Gladiators. Joe Moretti was the guitar player kind of responsible for that in the studio. It was Colin Green within the band.

The thing I’ve always loved about your tone, all through the years, is you’re able to get a lot of sustain without a lot of very heavy, fuzzy distortion.

Right, I think that’s the trick, really. Guitarists tend to rely too much on distortion to give them sustain. I think it has a lot to do with insecurity. Every time I go in the studio, I tend to overdo the sustain part. I tend to turn it up too much. Then I listen back a couple of days later and go, “No, too fuzzy.” You count on that distortion to give you more sustain. It’s much more forgiving. Whereas someone like Hendrix didn’t have too much sustain. He just made it work with a cleaner sound. At the end of the day, if you can get the results with a cleaner sound, it’s actually much better. I have noticed that a lot of guitarists today have so much compression and distortion on their pickups that it makes it sound thin and small. I don’t like that sound. It’s got to be somewhat open and natural. It’s just got to have an edge of distortion. Whereas now, with all these distortion units, people whack it up. They have infinite sustain, but the tone sounds like Mickey Mouse.

You’ve used a few different amps over the years to get your sound—principally Vox, Marshall and Engl, right?

I really loved my Vox sound, but I wanted to change to Marshalls for the look. I knew Jim Marshall very well. I used to go to his shop in Ealing, which was close to where I lived, and buy my guitars. I bought my 335 there, and funnily enough, Mitch Mitchell was serving behind the counter at the time. And I’d go to the Marshall factory in Bletchley, where I met Ken Bran and Dudley Craven, who devised the circuit for me in a Marshall setup. They’d be there with their soldering irons and I’d be batting away on the guitar trying to get the amp to sound like a Vox. I’d be playing so loud that all the women there, who were doing the construction of the amps, would storm out together, saying, “We can’t work with that loud nonsense going on.” Sixty people or so working there would leave the factory.

Then Jim Marshall would come in and say, “I knew you were here. I could hear you from down the road.” The office was a couple of doors down. He was very nice about it. “Carry on. I’ll get the women back in and working.” And then they devised a soundproof room that I used to go and play in. Because I was there so often looking for this sound. One of the secrets that they will deny to this day—’cause they told me they would—was that they could not come up with the sound that I wanted. I wanted this Vox sound which was very distorted and very cutting, but seemed to have a bass resonance. And they just couldn’t get that. So in the end they said, “What we’re going to do is get one of our combo amps and we’ll take out the innards and put in the Vox innards. So you’ll actually be playing a Vox, but it’ll say Marshall. That was the big secret of the day.

This was during the Deep Purple years?

Yeah, right in the beginning—1970. And then we kept going from there. The guys at Marshall were determined to get the right sound for me and they were very helpful. So what they did was put an extra output stage into one of their 200-watt amps, which gave it a fatter sound, a bit more distorted. This extra output stage basically made the 200-watt into a 280-watt. So for the first probably five years of Deep Purple—’70 to ’75—I did have the loudest amp in the world. Although I’m sure it’s dwarfed now by people who have a million watts. You know how it is. Everyone’s got to have one more, one more. Going up to—what?—11 now, I guess.

Oh, I think we’re on 12 now.

Exactly.

What about effects?

I don’t use effects. I’m from the old school of, “The more things you use on stage, the more things there are to go wrong.” But in the early days of ’69 through ’73, which would be “Smoke on the Water” time, I used a Hornby-Skewes treble booster. It not only gave me a bit more treble, it also gave me just a fraction of distortion. And that is the sound I always used, coupled with the Vox or the Marshall. For a while, Jon Lord used the Hornby-Skewes and Marshall for his organ as well. We were looking for a distorted organ sound and I said, “Why don’t we plug your organ through my Hornby-Skewes and into my amp and see how an organ sounds like that?” So we did it, and of course he loved the sound. And that’s the sound you hear, for instance, on “Smoke on the Water.” He played with that sound for about four years, then he went back to the Leslie sound.

But more recently, you’ve been using Engl amps.

Yes, the Rainbow tours would be Engls, which is a German amp. I was living in Connecticut when a friend of mine said, “Have you tried this little amp, called an Engl?” I said, “No, I just use my big Marshalls.” But I always preferred smaller amps. You could contain the sound more. I was used to that from they days when I used my Vox. So I tried this little Engl amp and I liked it. They started making these amps up for me and I’ve used them ever since.

At the other end of your musical universe, how did you first get interested in Renaissance music?

I think it started when I first heard “Greensleeves” when I was 10 years old. From there, it went in stages. I’ve always loved Renaissance music, more so than Medieval or Baroque. I’m talking about basically the 1400s to 1500s. Tielman Susato was a composer from that period who was basically from Antwerp. And I saw David Munrow and the Early Music Consort of London playing all the woodwind and brass instruments like shwams, sackbuts and crumhorns, and that just stirred my soul. I love the organic sound of all the instruments from that period—hurdy gurdys, bagpipes… I thought, I’m playing the wrong instrument here. So I started learning to play the hurdy gurdy and mandola. I have a couple of mandolas. I love picking up the mandola, which is tuned in such a way that it sings, and you’re immediately transported back to those days.

A lot of people are totally obsessed with the blues. I’m not. If I hear more than a couple of blues songs, I’ve heard enough relative minors. But the Renaissance music is a whole other world. It’s hard to explain. I don’t follow the orthodox way of playing Renaissance music. One would think I’d have to be into the lute bigtime. But I’m not. I’m more in love with the woodwind sounds of the Renaissance, which is peculiar, because I try to emulate that with an acoustic guitar and mandola. A Renaissance music purist would say, “Well, that’s not Renaissance music.” But no one actually knows what Renaissance music is actually like, ’cause they weren’t there.

It’s all theoretical—reconstructed from manuscripts.

Yeah, and there wasn’t too much printed music back then. Unfortunately, many people who play Renaissance music can be a bit snobbish. A lot of purists get bogged down in what “should be.” They’re into the proper schooling at Oxford or Cambridge. But, as I say, no one really knows what it sounded like in those days.

The Renaissance music world can be a bit academic.

That’s why I think people go into rock and roll. It gives them an escape from all the schooling—what’s “proper” and how it should be. I remember Jimmy Page getting into trouble when he used to do a lot of sessions. He said something like “classical musicians hate music.” I think that’s when he decided to leave session work and join the Yardbirds, because all the classical musicians on the sessions he played disliked what he’d said about them.

But it’s totally true. Whenever I’ve done anything with an orchestra, I always found myself dealing with a lot of chips on shoulders. You’re always too loud for them, no matter how quiet you play. I think it has something to do with, “These rock and roll performers like the Rolling Stones make so much money and we’re classically trained purists and we don’t make a quarter of that money.” I think there’s a resentment there.

I remember doing the “Concerto for Group and Orchestra” [1969] with Jon Lord. I was playing with my small Vox, but it was set next to the violinists, and you could see that they hated every note I played. ’Cause it was just too damn loud. At one point in the piece, I was given something like 24 bars of freedom to improvise around a few chords. And the whole orchestra was supposed to come back in after the 24 bars. Of course, I wasn’t counting 24 bars. I was just improvising. And the conductor was trying to hold back the orchestra from coming in, ’cause I had not finished my spot. I didn’t realize this at the time, but apparently I did something like 54 bars. And of course the orchestra was in total shock because I wasn’t sticking to the music. That caused chaos with them.

They’re very much tied to the printed score.

That’s right. That was the Albert Hall too. No one noticed until the conductor reminded me later. I said, “Wow, did I really go on that long?” I didn’t do too many of those after that, because I just found it very awkward—to have to play so quietly. And I’m not a schooled reader. I can busk my way through chord changes. When I used to do session work, way back, I had chord charts and I would be allowed to do a freeform solo or whatever. I was never one for reading note-for-note.

I asked James Burton if he reads music, and he said, “Not to where it hurts my playing.”

Exactly. A great guitar player, by the way. Deep Purple had a song called “Black Night,” and the main riff came from James Burton and Ricky Nelson. If you listen to their recording of “Summertime” from 1962, the bass is basically doing the “Black Night” riff across the song “Summertime.” That came out in a subliminal way when we wrote “Black Night.” We needed a hit record and basically wrote this track. And it turned into a number one hit for us.

That riff is also very close to “We Ain’t Got Nothing Yet” by the Blues Magoos.

People tell me that, but I don’t even know the Blues Magoos. I got it from “Summertime” by Ricky Nelson. I’ve always said that. It’s funny because the lead guitar part on that same song is the Hendrix intro to “Hey Joe.” If you listen to what James Burton is doing on guitar in the first three or four bars, it’s that. When I heard Hendrix’s “Hey Joe” for the first time I said, “Oh, I know where he got that from.” Whether he actually did or not, I don’t know. It’s a small world. I wouldn’t like to paint it.

Are there any current guitarists you like?

I’m not really listening to too much rock and roll these days. I find it sometimes feels a bit generic. I feel, “Well, I heard that years ago.” Although I think the standard of guitar playing is so high now. I was watching a documentary the other day called Hired Gun, and it’s excellent. I didn’t realize the guy in Pink’s band was such an excellent player. And there was Brad Gillis from the old Ozzy Osbourne days, and Steve Lukather and all these country players like Brad Paisley who are phenomenal. And I’m wondering, Where are all these guys coming from? Too much competition. I’m going back to Renaissance music. [laughs]

Well, they’re standing on the shoulders of giants. They’ve got a lot of rock history to play off.

That’s right. I think back to when I was starting and I’d listen to a solo by Cliff Gallup from Gene Vincent’s band and try to figure out the notes. Whereas now, not only are you told the notes, you get the video of how to play it on YouTube. It takes all the secrets away. All the things that you had to work so hard for are much easier to obtain. I’m not sure if that’s a good thing.

Do you think that has had a detrimental effect on rock?

I think, in a way, it does. Because where does that end? If everything is made too easy, it’s not fun. When I was starting, with an acoustic guitar, I’d put a pickup on it by the time I was 11. By the time I was 13, I had two pickups on it. My own wiring and everything. Whereas today, I think you can get a really good guitar for $100 or $150. It’s so available to everybody. I think they’re missing out on the hardship.

So you’re planning to do more shows with this new Rainbow lineup, but not a studio record?

That’s right. We can have fun playing, and it’s refreshing and we get our sleep. Because we do six or seven dates and that’s it. Then we wait another year and do another six dates. I want to go play in places that I’d like to visit, have a look around, stay in a few castles and have a good time. I always read the guitar magazines when I travel. And I always get a bit nervous because I read about so many brilliant guitar players.

But there’s only one Ritchie Blackmore.

So I’ve heard. Actually, I’ve heard there’s three. There are people out there who go around saying they’re me. This one guy was in hospital and he was telling everyone that he’s me. They have surveillance pictures of him doing it. So the police called me and said, “Is this really you? Are you okay?” Very bizarre. I suppose it’s flattering in a way—the price of fame, I guess.

Source: www.guitarworld.com