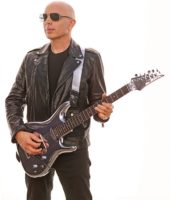

Joe Satriani Talks 'What Happens Next,' His Back-to-Basics New Album with Glenn Hughes and Chad Smith

Ever since his recording career began in 1986, the guitar virtuoso has worked fanciful concepts throughout his albums—there was time travel and intergalactic space themes; there were Silver Surfers and gigantic rock robots; and even Satriani himself got caught up in the act, assuming various guises and alien personas, such as Professor Satchafunkilus and Shockwave Supernova. As the conceits piled up, the music became more elaborate, with an emphasis on extended arrangements and shifting time signatures. For Satriani, it was all becoming a bit too much.

“Eventually, you just have to summon the nerve to close one door and open another,” he says. “I think I knew it on the Shockwave Supernova album. It was a definitive coming together of artistic explorations that had lasted a couple of decades, but I did end it with the track ‘Goodbye Supernova.’ At first I didn’t think it was such a heavy statement; it was just a song that encapsulated the narrative of the album. But as we played it on tour every night, it was cathartic. I started to realize that I was breaking away from the past.”

He pauses, then adds thoughtfully, “I wanted to get my brain out of the cosmos and get back to being a guitar player with two feet on the ground. I wasn’t trying to reinvent myself as much as I was trying to return to something that I was—me.”

Satch laid out his plans for the new album in a text he sent to his old pal and Chickenfoot bandmate Chad Smith (also the drummer for the Red Hot Chili Peppers): “No odd-time signatures, no progressive stuff, pure rock and soul.” Smith was in immediately. And then the guitarist had a wildcard idea to complete the studio trio—Glenn Hughes. The onetime Deep Purple bassist and vocalist (and current frontman for Black Country Communion) was already chummy with Smith—the two have recorded together over the years—and Satriani had a feeling they would make a dynamite rhythm section for his latest endeavor.

“Deep grooves were very important on this record, so I needed players who could funk and rock,” Satriani says. “I grew up on that, and it’s something I miss. Everything in rock has gotten so stiff over the years. Glenn was part of the fabric of rock that had funk and soul in it, and obviously Chad lives and breathes that stuff. They knew exactly what I was looking for, and they were right on the money the whole time.”

The album’s title, What Happens Next, is as direct a statement as Satriani has ever offered, and the same can be said about its songs. There are relentless, riff-o-matic rock behemoths (“Energy,” “Headrush”), wild funk stompers (“Catbot,” “Super Funky Badass”) and laid-back groovers (“Righteous,” “Smooth Soul”). Everything is illuminated quickly and efficiently, but that’s not to say Satriani’s perfectly crafted songs lack dimension or surprises: When “Cherry Blossoms,” a transfixing ballad built around an elegant Santana-esque melody, suddenly explodes into schizo guitar rock, the effect is shattering, and this feeling is heightened because the moment feels completely spontaneous.

“I wanted everything to hit hard but still have those unexpected ‘oh, wow!’ moments,” Satriani says. “And more importantly, I wanted it to sound like three crazy musicians making noise together. I have to give my producer, Mike Fraser, a lot of credit. He gave us just enough room to go nuts, but he always kept his eye on the original idea of each song.”

In your text to Chad, you wrote “no progressive stuff.” But whenever you touched on that genre in your music, it never sounded like true prog. It didn’t sound like math.

Yeah, well, that’s not me. I always keep it real and natural—I try to, at least. Even when I dip into the blues or jazz or something, you can hear that I’m not co-opting or culture raiding. I’m still a rock guitarist.

Did the state of the world ever enter into your writing? Songs like “Cherry Blossoms” and “Forever and Ever” are so touching and wistful. Were you thinking, People need this right now?

Oh, yeah. Escape. The world needs escape. I know I do. I never put on music to remind me of how terrible the world is or to digest the subtleties of politics. I put on music to make me feel good or to make me forget what is happening. Yesterday I was painting, and I think I listened to the new TV on the Radio album 20 times. It just put me in this great place.

So yeah, there’s heartfelt stuff on the record that takes you somewhere warm and nice, but then I have stuff like “Energy” that just rocks—and that’s another kind of escape. It’s that feeling of being super-excited and having positive energy pulsing through your hands. And I want to spread that around.

Do you still think about technical breakthroughs on the guitar when you write, or is the focus solely on composing good songs?

No, I’m still excited about that. I’m still a little kid in the candy store when it comes to doing crazy things with guitars and amps and pedals. In the demo for “Cherry Blossoms,” I was really shredding in the solo—it was nuts. But when I listened back to it, it sounded embarrassing. There were too many notes; it sounded like I was just showing off. So I told the guys in the studio, “I want to do something different there.” They were all in agreement—“Okay, do something different, but don’t suck.” [laughs] So I plugged into a whammy pedal and a Micro Pog, and I think I had a Twin Bender into an old ’71 Super Lead Marshall head, and I just went for it.

The sound was totally freaking out. I’m doing all these crazy things, manipulating the pedals and going back to the guitar. The guitar was just ringing out in this ambient way—it was cool and strange. I must have looked like an idiot to the guys in the control room, but when we all listened back to it, the stuff I was doing sounded really striking. But the reason I got there was because what I did on the demo just didn’t work, the shredding stuff.

I asked that question because a portion of your fans still want to hear “Joe Satriani, guitar hero”—like when they go to guitar clinics.

“Show us the crazy stuff.” Sure, I get that. It’s always a balance. Some of the more technically minded people want to hear that, but I think the majority of the audience just wants to hear music. I imagine that some guitar players might hear a song like “Righteous” and think, That sounds so simple. Anybody can play that. Then I’ll go, “Okay, let me see you pull it off.” What sounds easy isn’t always easy.

That song reminded me of classic Al Green.

Oh, that’s great! It’s from that period of music that was flying around when I was a young guitar player. I grew up with so much soul music in the house, Al Green in particular. When you live in a house of seven people, everybody listens to what everybody else has. I was the youngest, so as people started leaving, a lot of records got left behind.

I imagine there was some Sly Stone in the house, too. “Smooth Soul” sounds like Sly.

Sure. That’s Sly Stone, Curtis Mayfield, Carlos Santana—I’m waving a big flag, saying, “You guys are awesome!” “Smooth Soul” sounds easy but was difficult to play. Songs like “Energy” and “Head Rush” are easy to play—they just push you along—but stuff like “Smooth Soul” and “Righteous” can be challenging. The weight is entirely on your shoulders and how you finesse the melody.

Obviously, you’ve played with Chad a whole bunch. Glenn Hughes is an interesting choice: He’s primarily a singing bassist, not a studio bass player.

And that was a concern for me at first. I didn’t know if he’d be willing to not sing—I didn’t want to hurt his feelings by asking him that. And he even said to me, “Are you sure you want me to just play on this thing?” But I said, “Yeah, it’ll be fantastic,” because I knew he and Chad were already tight. And I gotta say, within the first 10 minutes of playing with the two of them at Sunset Sound in Los Angeles, it totally confirmed my feelings that this was the right move. The ideas coming from them as a rhythm section were fantastic.

Chad and Glenn are both equally adept at rock and soul. Did they make you dig into your rhythm playing differently?

They did, and I needed it. I wanted players who could fill the spaces and make them exciting but not technical—and you know, that keeps me on my toes. Like a lot of this stuff, it sounds easy in principle, but you really need the right guys to pull it off.

I’m sure you didn’t have to explain to them the stone-cold grooves you wanted for “Catbot” and “Super Funky Badass.”

No, not really. “Super Funky Badass” is pretty straight ahead, but “Catbot” is kind of weird. “Rock and soul” was definitely the phrase I used with them a lot. Because I didn’t want to scare them away thinking, Here’s this song in 17/8, and you gotta play this pattern exactly like my demo or something like that. I let them move around.

On “Thunder High on the Mountain,” you do some hammer-ons, but they’re an essential part of the melody. A lot of people still use that technique as a flashy trick.

Yeah, it’s funny isn’t it? I don’t start out thinking that I’ve got to do hammer-ons. Sometimes it happens by accident onstage: The spotlight hits you and you lift up the guitar—“Hey, look at this!” But when I’m writing, I’m kind of singing a melody and thinking, How many ways can I get this across? With that song, I tried it with the hammer-on thing and it sounded interesting. But I’m never trying to get any particular technique into a song—it never works that way.

Overall, there’s a stripped-down quality to the sound on the record. Did you use less gear and fewer guitars this time?

I did keep it lighter than usual. I’m not signed to Marshall anymore, but I did use my JVM410—the HJS. I think Marshall is still selling them. Eighty-five percent of the time, that was the head I used for melodies and solos. I also acquired an MZero from Mezzabarba that’s pretty cool. I used a few vintage Marshall heads from between ’67 and ’75, and there were a couple of old Fender combos.

I had three guitars that pretty much did everything. I had my number one Ibanez MCO—that’s the prototype for the orange JS2410—and then its brother, the DMCP. My Ibanez JS25ART guitar sounded pretty great on everything. Those were the main ones. There were some bits where I used a Custom Shop ’69 Strat, and I paired that with a Custom Shop Flying V. Funny, though, I still can’t figure out how to sit down with a V. [laughs]

Did you use new effects in the studio?

There was definitely one that I found really exciting—the Sola Sound Tone Bender, the MKII. That thing just totally blew my mind. I think Sola Sound has a cease and desist order against them, so I’ve been scouring the world trying to buy up various things. I also used a Ramble FX Twin Bender, which is a cleaned-up version of the Tone Bender. What else did I use?… A little Voodoo Vibe and the Strymon El Capistan—that’s a great little echo. Of course, there’s a little Pog and Micro Pog. There’s one song, “Looper,” that’s almost entirely SansAmp. So, you know, some new stuff.

You recently turned 61, yet this album sounds just as youthful as Surfing with the Alien.

Yeah, that is odd. What can I say? I feel 61, but hey, I’m pretty happy to be here. [laughs] I’m also happy to take this shift in subject matter. I think that really helped with the energy behind the whole record. When you’re excited, it’s gonna come out. I hope people can hear that.

Source: www.guitarworld.com