The story of Brian May’s Deacy amp, the little amp that could

Brian May is responsible for one of the most iconic and influential guitar tones of all time, evident on his many mammoth hits with Queen. Most players are familiar with May’s Red Special, the unique home-built guitar that May has used throughout his career. But less known is another integral bit of gear from the Queen studio: a tiny home-built amp known as the Deacy.

READ MORE: Watch the new video for Brian May’s On My Way Up

While Queen’s tone was massive – probably the definitive arena rock sound – May’s gear had humble beginnings. The Red Special was constructed mostly from items found around May’s home, including wood from his mantelpiece. The Deacy, meanwhile, started life in a London dumpster.

The story goes that shortly after Queen bassist John Deacon joined the band in 1971, he was walking along a London street when he spotted a cluster of bright electrical wire sticking out of a dumpster. As an electrical engineering student with a penchant for tinkering, the wires warranted a closer look. Deacon did some digging and found that they were connected to a circuit board. Once he returned home, he noted that the board seemed to be from an old radio.

Deacon then retro-fitted the circuit board and wiring into a small cabinet that housed two speakers, including a 6.5-inch Elac Twin Cone. He installed a quarter-inch input jack and a volume knob, the latter later removed when he discovered that the makeshift amp sounded its best when turned all the way up. The whole unit was powered by a brick-sized PP9 nine-volt battery pack.

Deacon initially used his creation as a practice amp for his guitar, which he played alongside bass and keyboards (he played rhythm guitar on the 1982 Queen track Staying Power). Eventually Deacon brought the amp to the band’s rehearsal space to show it off. Then May, famous for using a treble booster with a single-transistor circuit – in those days the OC44 germanium transistor-based Dallas Rangemaster – plugged in…

Stoked by the guitarist’s renowned high-attack play style and combined with his treble booster and Red Special, it became clear that the Deacy was the final piece of the puzzle. Queen had discovered their famous tone, one we’d be left chasing for decades to come.

The Deacy timeline

May quickly adopted the Deacy and used it on tracks such as 1974’s Killer Queen. This was a time when 100-watt Marshall stacks lined stages and tube-amp power reigned supreme. The Deacy, however, had an output of about 1.5 watts, so it was never intended to be used on stage. May found it perfect, however, for studio recording.

The Deacy’s sound characteristics sat differently in the mix to those of the Vox AC30, for example, especially in the way its sound combined with its own overdubbed harmonies. May described its sound as “symphonic”.

May used the little amp from the 1970s until the 90s and, unlike most amps, the Deacy, unburdened by complexity, never failed to deliver a consistent tone. It was a solid-state design and had no tubes, which made it more durable than a tube amp. According to May, it never malfunctioned.

In 1998, during the months when he was tasked with restoring May’s Red Special, Australian guitar and amp-maker Greg Fryer became the first to open up and examine the Deacy in detail, at May’s Allerton Hill studio. In June of that year, Fryer asked David Petersen, historian and co-author of 1993 book The Vox Story: A Complete History of the Legend, to collaborate with him and build three Deacy replicas for May’s studio.

The replicas were good but didn’t sound the same as the original. It would be a while and many secrets later before the Deacy would finally unveil its tonal mysteries.

The Deacy amp’s PCB

In July 1998, Fryer spoke to John Deacon about the origins of the Deacy, with its maker’s information shedding light on the amp’s unusual origins. When Fryer then returned to Sydney in late 1998, with May’s blessing he continued his research into the Deacy and made further experimental prototypes.

Years passed and, in 2003, Fryer asked UK electronics expert Nigel Knight to assist with his Deacy research project. Their objective was to eventually build May-endorsed Deacy amps that would complement Fryer’s Brian May Treble Booster range.

In 2008, Fryer and Knight finally formed a partnership to make the Brian May Treble Booster and Deacy Amp, as well as other products. Incredible attention was paid in crafting the Deacy amps as genuine copies of the original – custom transformers had to be created from scratch to the exact winding and laminate specs of the original.

Celestion later joined the project and produced dozens of prototype versions of the Elac 6.5-inch twin cone speaker, until eventually settling on a final version given the nod by May.

Then, 12 years after the project’s inception, in 2010, the Brian May Deacy Amp replica was given the official stamp of approval by May and Deacon. The replicas were highly sought after at the time and, since the model has now been discontinued, are perhaps now even more so. May even used the replicas on the road for a while.

Elac Twin Cone Speaker

Long may it reign

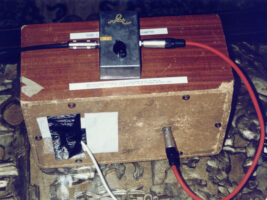

There have been many clones of the Deacy. But the original remains in use and is perhaps the simplest amp in the world – no control knobs, just a plug-in for the battery pack and a quarter-inch input jack.

For decades, it remained an enigmatic piece of gear. Speculation in forums was rife about its lineage and components. Back then only one thing was certain: it was an integral part of May’s tone. Even today questions remain…

What was the origin of the circuit board that Deacon dug out of that London dumpster? This would remain a mystery until 2013, long after the original Deacy had been opened and replicas produced.

The Deacy amp during the recording of Another World in 1998

The board would eventually be linked to the amplifier section of a transistor radio called the Conquest Supersonic PR80. An obscure product in the first place, they were built in South Africa and Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). These early/mid-1960s amps used germanium transistors, long known to be temperamental, expensive, and noisy in the preamp stage, and later largely replaced by silicon transistors.

Despite being infamously inconsistent, the germanium transistor in the Deacy seems to have been remarkably resolute, responsible for decades of continuously powerful sound. Queen have long been a quintessential arena rock act – the irony is that the band’s massive tone came from one of the smallest amps around.

For more features, click here.

The post The story of Brian May’s Deacy amp, the little amp that could appeared first on Guitar.com | All Things Guitar.

Source: www.guitar-bass.net