Master Class: The John Petrucci Guitar Method

There are certain people in the world that gravitate toward creative outlets. You will find that a lot of musicians also like to draw, paint and write. There’s a common thread that if you are someone that not only has a “want,” but also a “need” to be creative, hopefully you’ll be lucky enough to find music as an outlet for expression. I was fortunate to find music at an early age, at a time when I was also interested in painting, drawing and the visual arts. I found that I gravitated toward the guitar, for whatever reason.

When I was growing up on Long Island, it seemed that just about everyone I knew played an instrument, and there were so many bands. You could literally walk down your street and hear garage bands playing, and there would be “battle of the bands” contests at school. There was a lot of guitar-driven music on the radio; all the rock stations would always be playing Led Zeppelin, Boston, AC/DC, Ozzy and Black Sabbath. I always knew I wanted to find a way to channel my creativity, and the guitar and music became the way in which I was able to do that.

When I was young, I had this recurring dream in which I was onstage playing guitar. This was before I was ever in a band, but it drew me in, even before I knew what was happening on the instrument. I’d hear things on the radio and had no concept of how the musicians were making it happen. I’d hear the two guitar players in Iron Maiden playing harmony leads, but I didn’t know how that worked. When I played, I’d think, Where’s the other part? I remember hearing Eddie Van Halen employing different playing techniques, like fretboard tapping, and thinking that it didn’t even sound like a guitar. I had no idea how that was being done, but I was drawn to it. And I loved hard rock and heavy metal—it just hit me, and I loved it. I loved Maiden and I loved Metallica.

As I became more proficient on the instrument, I began to investigate guitarists that played outside of rock and metal styles, and that’s when I got into Steve Morse and the Dixie Dregs, and Al Di Meola with Return to Forever and his own recordings, and Allan Holdsworth too. I ended up combining all of these influences in my own playing. Two bands in particular that gave me those “wow” moments—like, “I really need to learn how to do that!”—were Rush and Yes. These bands, and especially their guitarists—Alex Lifeson and Steve Howe—became huge influences on my playing and songwriting style and on my approach to orchestrating guitar parts. If you look at Dream Theater now, we have the same instrumentation as Yes, where the guitar and keyboards are the essential parts of the bigger, orchestral, progressive rock sound.

FIRST RIFFS

I remember that, when I first started playing the guitar, it was impossible for me to play even the simplest things. Many guitarists will tell you that it’s not necessarily an easy instrument to get started with. For instance, when you play piano, you can just lay your hands down on the keys and make musical sounds. On guitar, there’s a learning curve of developing hand coordination and strength; even playing basic barre chords is a challenge at first.

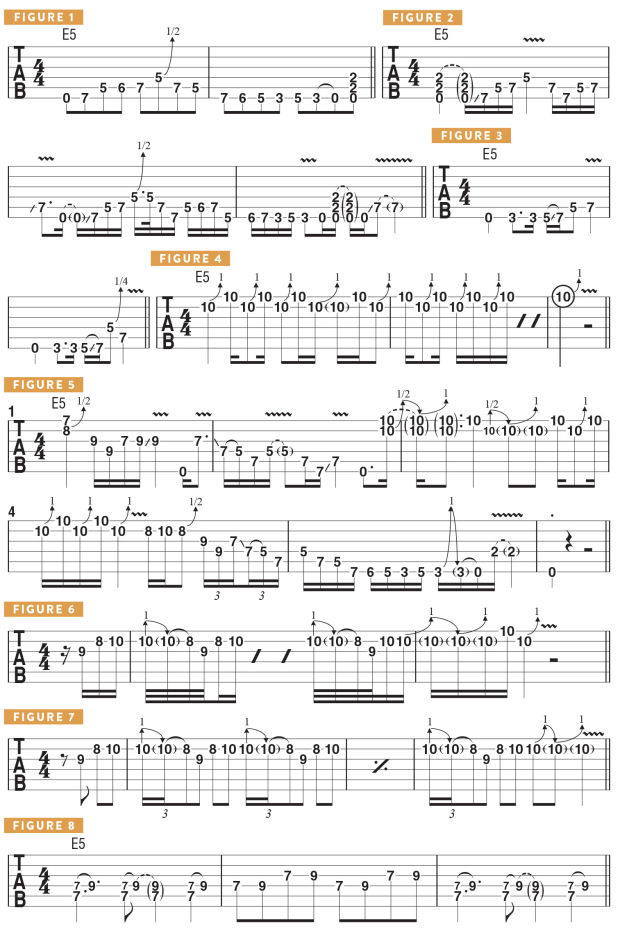

Everything that I played in the beginning was not very complicated; I’d play licks like this (FIGURE 1), based around the E minor pentatonic scale (E G A B D). The Zeppelin and AC/DC stuff was in that zone, in the basic keys (FIGURE 2). Early Rush is in the same bag (FIGURE 3). The first Rush album was all Zeppelin-inspired trio stuff with extended guitar solos and in that vein—single-note bluesy rock.

I remember trying to emulate some basic guitar solo stuff that Alex Lifeson would do. It would sound great if you simply kept repeating the same lick over and over (FIGURES 4 and 5). There’s always room for licks like that! I would try to perfect things like this (FIGURES 6 and 7).

Even with something simple like this, when I first learned it, I had slowed down a guitar solo with my turntable set to half speed (16 rpm), and I could hear the notes, but I’d think, why don’t they sound right when I play them? It wasn’t until I discovered that there were string bends involved, and in fact ghost bends—pre-bending and releasing notes—that made the lick sound right. And why is there a growl sound when you play the bent A note and the high D together? You make these discoveries when you see someone else do it, or when you stumble upon it yourself.

I remember trying to play “Paranoid” by Black Sabbath, and I saw a garage band play the song and the guitarist did this (FIGURE 8), hammering onto the note on the D string, and I thought, Holy crap! That’s it! I was missing that hammer-on, and I knew something didn’t sound right. You discover those little secrets that slowly begin to unlock how to do these things on the guitar, and it becomes a little less mysterious, driving you onward to learn more.

VIBRATO

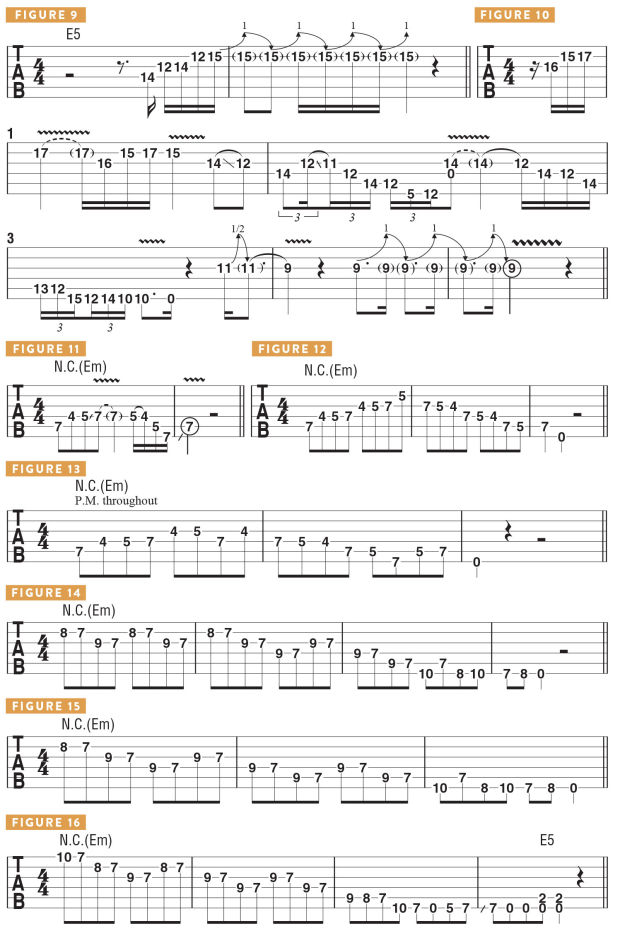

Vibrato was a technique I had to learn in and of itself. I’d hear it, but I didn’t know what it was or how to perform it. I was learning an Iron Maiden solo one day, with the record slowed down to half speed, and Adrian Smith played something like this (FIGURE 9). Slowed down, the vibrato sounded like this huge, repeated bend. Light bulbs went off! That’s how you do it! I realized that, to create vibrato, you bend up from one note to another note, back down and up, and that’s how to get that sound (FIGURE 10).

In the beginning, like when learning an Angus Young solo in an AC/DC song, I’d have the right notes, but it was another thing to emulate Angus’ cool, distinctive vibrato. Either someone has to show it to you, or you have to see someone do it, or you simply stumble upon it, like I did with the Adrian Smith solo.

Vibratos are like fingerprints—everyone’s vibrato is a little different, and everyone approaches the technique a little differently. If you try to mimic the signature vibrato of a certain player, just that is enough to bring to mind that player to those familiar with his sound. You don’t think about vibrato too much when starting out, though.

ARTICULATION

Another “learning curve” thing is “how do I make what I play sound good?” There are so many things one can do to make it sound bad, such as pressing down too hard on the strings, making them sound out of tune, or slightly bending a string when you shouldn’t be, or not using vibrato when you should. If you play a simple line like this (FIGURE 11), you can make it sound boring by adding no inflections, articulation or vibrato, and you can make it sound bad by pulling the strings out of tune or allowing other strings to ring. The guitar is tricky that way. You really need to listen closely to your articulation in order to make what you play sound as good as possible.

When I’m moving from note to note in a melodic line, I don’t want the previous note to continue to ring. And when using distortion, especially, the potential for unwanted noise is that much greater. Even when playing a simple scale (FIGURE 12), you have to be sure to prevent the strings you aren’t playing from ringing. If I play a lick on the lower strings (FIGURE 13), I’m using the undersides of my fretting fingers to mute the higher strings. And as I move to the higher stings, the tips of my fingers mute the adjacent lower strings.

PALM MUTING

Everyone holds their pick a little differently, and I like to rest my pick-hand pinkie on the higher strings while laying the edge of the palm across the lower strings near the bridge saddles. In this way, I’m only exposing the string that I am playing on, and the strings around it cannot ring. The opposite would be a “floating” technique, wherein the picking hand doesn’t touch the strings at all, other than the pick striking the strings (FIGURE 14). When I pick normally (FIGURE 15), I feel more in control over the strings that I’m not playing. The physical technique is subtle, but it will make a huge difference in the sound. With metal and rock playing, distortion is often at a high level, so the danger of unwanted sounds is that much greater. To take it a step further, when you’re recording with headphones on, you become highly conscious of every little detail (FIGURE 16).

POWER CHORDS

From my perspective, there are two conceptual approaches to playing chords, one that addresses playing with a clean tone and the other that applies to using distortion. In regard to playing with distortion, I took my cues from two different sources and ultimately turned it into my own thing.

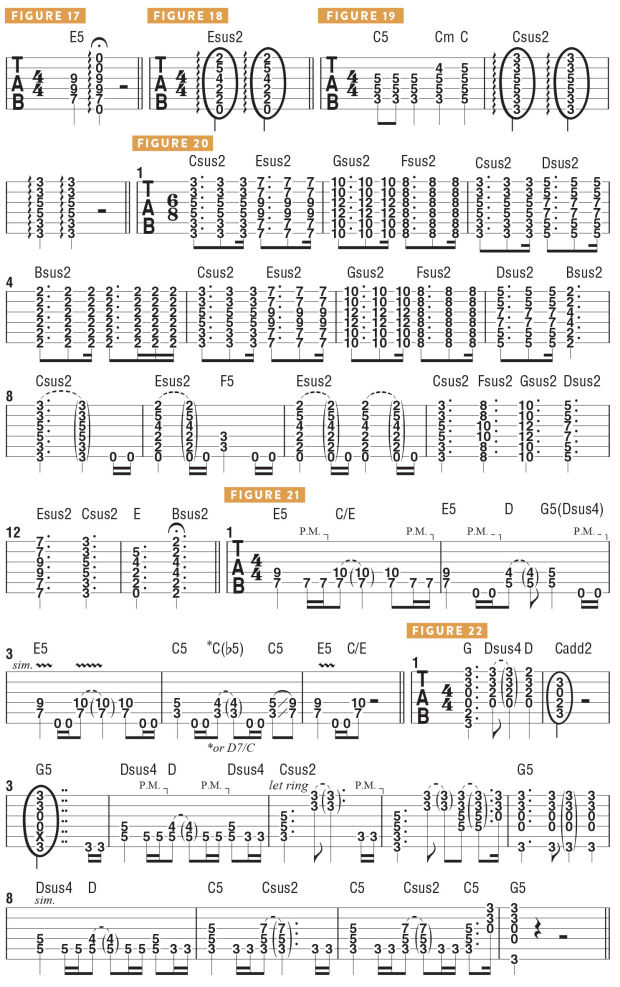

The first source was Rush and listening to how Alex would play big, extended open chords that made the guitar sound huge in a trio setting. That could mean playing more notes than you’d usually play. When playing an E5 power chord, Alex might add the open strings to create a larger sound (FIGURE 17). We can move down to second position and add the fifth, B, on the A string, and the ninth, F#, on the high E string, to widen the sound of an E power chord (FIGURE 18).

The other concept is adding a second, or ninth, on top of a basic barre chord shape. If I play a C5 power chord (FIGURE 19) and add my middle finger, I get Cm. If I barre my pinkie across the D, G and B strings, I get C major; but if I barre with my index finger, I get a “neutral” variation that adds the second, or ninth, D, on top of the C5 voicing, resulting in Csus2. Including the low fifth, G, with the index finger and strumming across all six strings creates a huge-sounding, Rush-style Csus2 “power chord.” You’ll hear these chords on “2112.” Just moving this voicing around the fretboard instantly yields a prog-y, Rush-like sound (FIGURE 20).

The second influence on my chordal approach involves double-stop chords played with distortion that serve to add more tonalities to the chords than just root-fifth or root-fifth-ninth, such as a flatted fifth, or a suspended fourth, or a major third. That influence came from listening to early Queensrÿche (FIGURE 21). I employed this approach in Dream Theater compositions like “Metropolis.” Using just two notes, I can move from a root-fifth E5 power chord to an Esus4 with an E and an A note. If the song called for Dsus4 to D, instead of using standard first-position open chords to get that sound, I can achieve it with two and three notes in “power chord” fashion (FIGURE 22). I’m implying the tonality in a sonically economical way and don’t need any other accompaniment.

I can create a two-note progression that moves between the fifth, the fourth and the major third (FIGURE 23). We can now add the flatted fifth to the mix, and you have all the ingredients to create a heavy riff (FIGURE 24). Here’s a riff from “Metropolis” that illustrates this technique (FIGURE 25).

If we look at these four pitches—the major third, fourth, flatted fifth and fifth—in E, they occur in a chromatic sequence on the D string, which could be a riff unto itself (FIGURE 26).

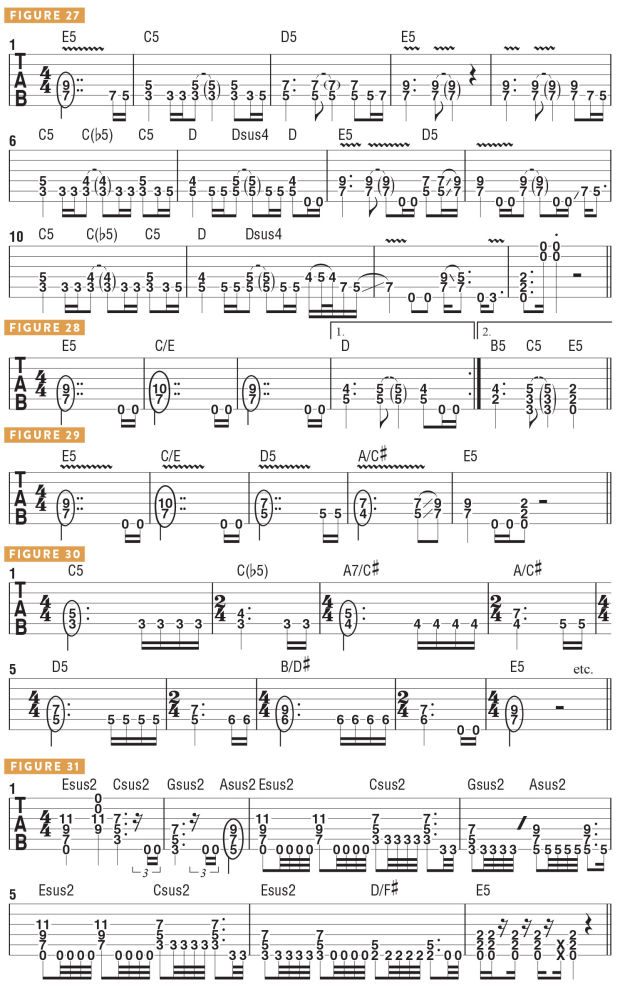

Using the chords Em, D and C, I can incorporate those intervals to reflect this chord progression. So now, something as simple as a straight E5-C5-D5 progression can sound much richer and more interesting (FIGURE 27). It’s still a basic progression, but the guitar sounds bigger while the part also provides more harmony and musical information.

If I take the E root-fifth shape and move the fifth up a half step, it turns into C/E, with the higher of the two notes now functioning as the root and the lower note as the major third, what’s known as first inversion. There is some mystery to this sound because the lower of the two notes doesn’t change, creating a “pedal tone” type of sound (FIGURES 28 and 29). This is such a great technique, one that helps to add more movement and tonality to a rock/metal-type riff. For example, I can move up and down the fretboard between C5 and E5 power chords by using a series of different two-note shapes, like this (FIGURE 30), which gives you a Metallica-like sound.

EXTENDED POWER CHORDS

The culmination of all of this is how I expanded on these ideas to create my own thing. To the big Rush chords and the Queensrÿche interval idea, I added a third note on a higher string. Going back to the Rush sound of the sus2 chords sounded with an index-finger barre (FIGURE 20), instead of sounding the F# over E5 on the B string, it’s fretted on the G string with the pinkie. I can then take this symmetrical three-string shape and move it all around (FIGURE 31). I use these root-fifth-ninth three-string shapes all the time.

If I move my pinkie up one half step, from F# to G, I now have an Em chord. If the progression goes from Em to Csus2, I can use these “spread-voicing” shapes, which sound better than conventional barre chords (FIGURE 32). If you move the pinkie up another half step, from G to G#, you get a major third and can sound an E major chord this way. In this example (FIGURE 33), I’m combining these shapes to create a great-sounding chord progression that has a built-in melodic line while keeping the root note in the bass.

Another cool twist is to change the lower note to the flatted seventh, what’s known as a third-inversion chord: with the E note at the seventh fret of the fifth string, I can add A#, fourth string, eighth fret, and F#, third string, 11th fret, while keeping the open low E in the bass (FIGURE 34). That sounds mysterious and creepy, and it has a metal, progressive sound to it that evokes a certain kind of emotion. Using these few chord shapes, you can automatically create riffs that sound cool (FIGURE 35), and in this example I’ve added a B7/D# chord to develop the musical progression a bit further.

POSITIONAL SCALE NAVIGATION

When I practice, I like to try and cover as many bases as possible with a single exercise. With this specific approach, one can apply it to all different types of scales in all keys. That’s the beauty of the guitar—all of these patterns are easily moveable. These exercises get you familiar with learning chord shapes while also working on specific picking techniques.

Steve Morse once said that whenever he needed to work on a technique, he’d devise a piece of music designed to address that technique, in the same way that classical etudes are intended. This makes the endeavor so much more interesting: not only are you learning specific scale shapes, you are also playing music while advancing your technique.

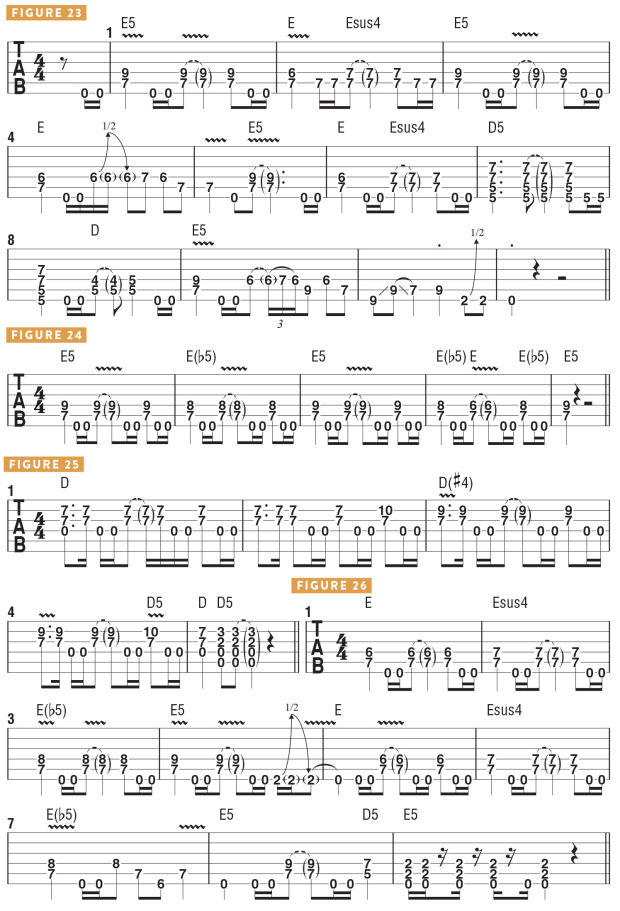

Let’s stay in E minor, starting in seventh position: set a metronome to a 16th-note click and play the scale ascending and descending, using alternate picking (FIGURE 36). Now let’s move through the different patterns, starting with one note per string, followed by two, three and four notes per string. This will address most of the variables you will encounter.

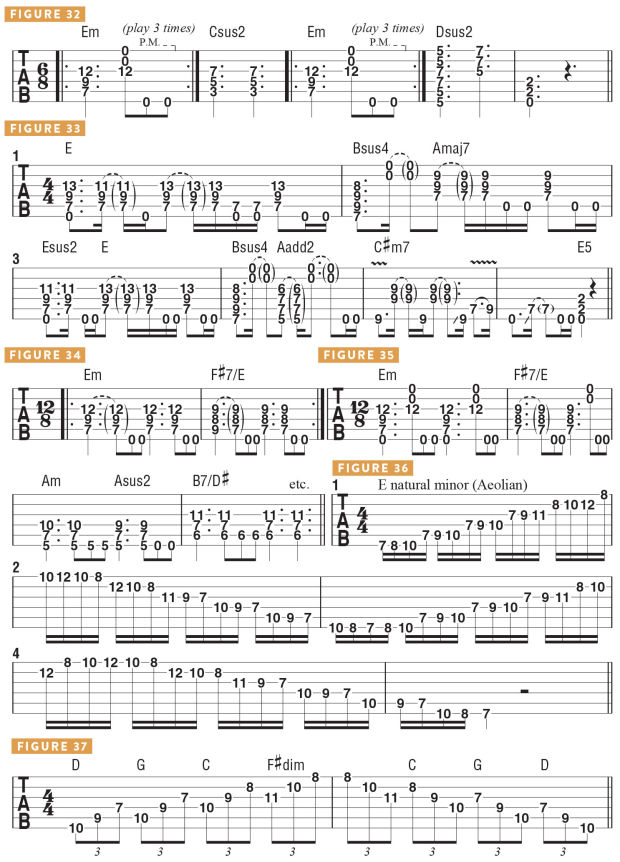

To apply the one-note-per-string concept, you need to identify the arpeggiated triads that fall within the scale as played in this position, starting from the highest note on the lowest string within each three-string group (FIGURE 37). I like to change it up a little bit to make it more interesting by adding a fourth note on the highest string, a third above the preceding note, followed by the two lower scale degrees, resulting in triplet patterns that alternate between three ascending notes and three descending notes. Here it is in ascending form (FIGURE 38). The progression of chords outlined is D7-Gmaj7-Cmaj7-F#m7b5, all chords living within the key of E minor. The descending form would be this (FIGURE 39).

You can play this pattern as eighth–note triplets, but you also can play it as straight 16th notes (FIGURE 40). It’s good to play through the pattern both ways, “hearing” it as both triplets and straight 16ths. Once you have a grasp of this approach, be sure to apply it to E natural minor (A F# G A B C D) in every position, and to every other scale you know in a wide variety of keys (FIGURES 41 and 42).

The next incarnation of this idea is built from a pattern with two notes per string (FIGURE 43). This is played in straight 16th notes, starting with a one-note pickup, which is the major seventh of the chord. The progression outlined is Cmaj7-F#m7b5-Bm7-Em7-Am7. This is another great alternate-picking exercise, and the line has a nice melodic contour. The cool thing is that all of these chords are built from our parent E natural minor scale pattern in this position, but arranging the notes in these arpeggios describes a chord progression. Practice the reverse version as well, and then play the pattern ascending and descending (FIGURE 44).

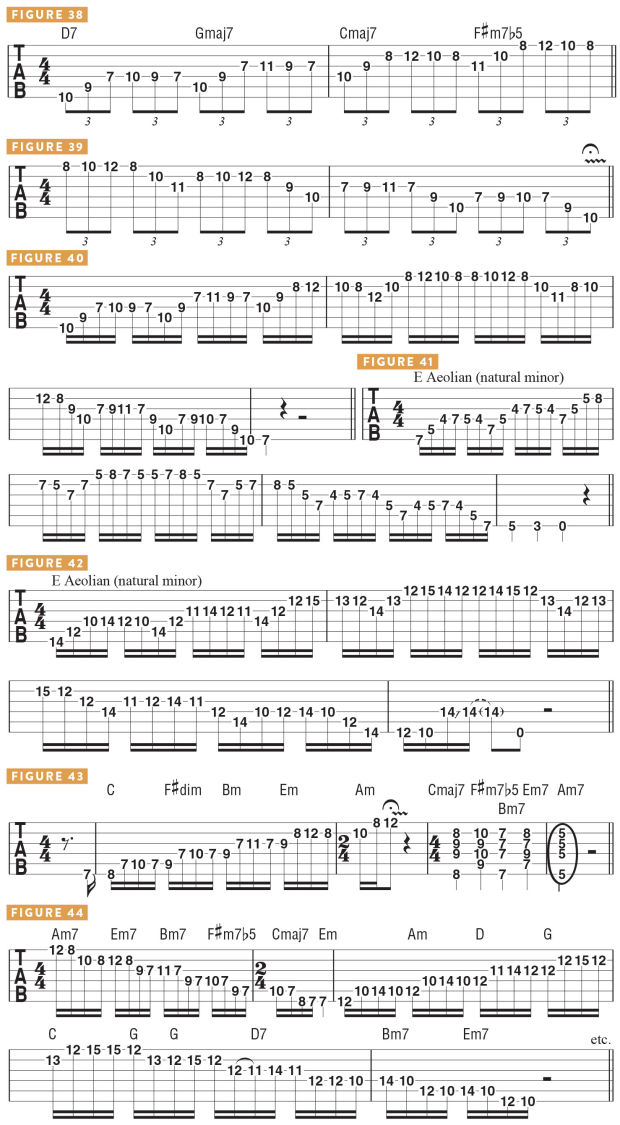

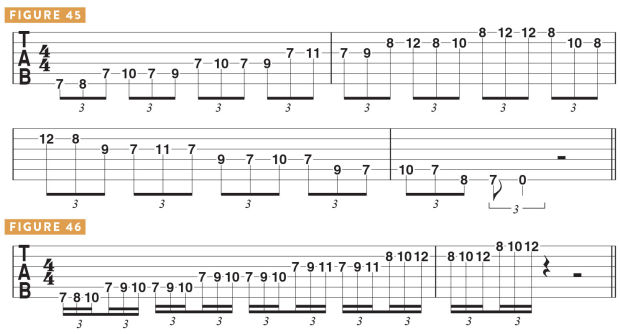

Since this two-notes-per-string pattern falls naturally into 16th-note groupings, play it as eighth-note triplets too (FIGURE 45) in order to get the most out of the exercise.

The third approach involves three notes per string, and this is a great way to practice sequencing as you move through a scale. Three-notes-per-string is probably the most typical way guitarists like to practice scales, but here we’re going to create sequences of six notes (FIGURE 46). Begin by playing the first six notes of the scale in order, low to high, starting on the bottom two strings. Then move to the fifth and fourth strings, playing these scale tones in the same manner. Continue this approach through all pairs of adjacent strings, playing the patterns as 16th-note triplets. You can try this pattern played as straight 16th notes too.

One of two ways to move back down through the string pairs is to simply play the pattern backward, starting on the highest note in each string pair, which is the most logical. A great twist is to play the pairs ascending, as we had done, but moving from the higher string pairs to the lower ones.

The fourth incarnation is built from playing four notes per string and, in order to keep this rooted in a specific position, I incorporate an extra note on each string, a passing tone, that is outside the scale. Each of these exercises forces you to sharpen your alternate picking technique. With one note per string, you will use a downstroke on one string followed by an upstroke on the next, which is the hardest technique to master. Two notes per string is more evenly regulated, as you pick down-up on each string as you move across the strings and your pick ends up in the same spot every time. The third version, three notes per string, is like the first because there’s an uneven number of notes on each string, so your picking direction constantly reverses—down-up-down, then up-down-up, etc.

This last incarnation—four notes per string—is evenly picked down-up-down-up on each string, but with more notes played per string. This is easier than picking two notes per string, because you’re not crossing strings as frequently.

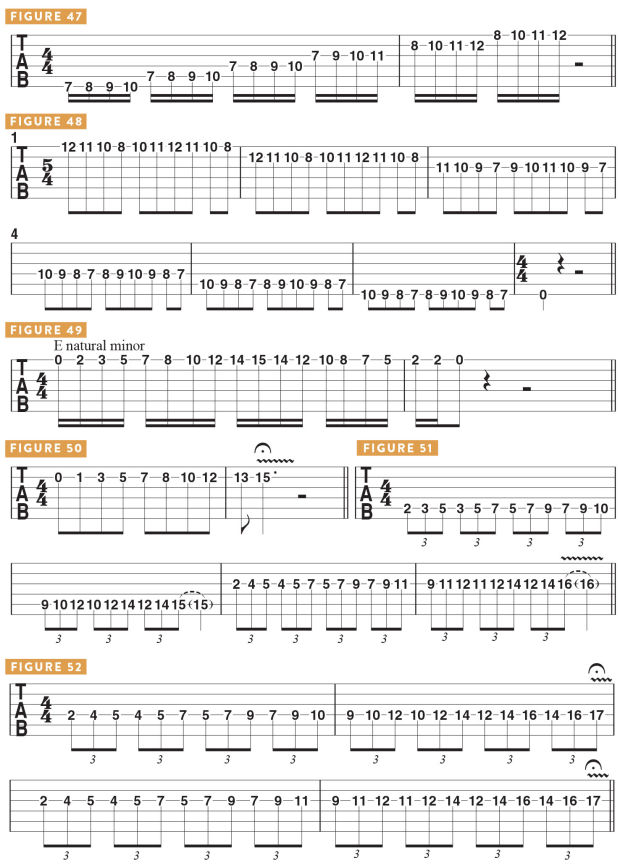

In adding the passing tone, in the instances where the three scale degrees fall between four frets, you simply add the “in between” note. On the sixth string, for example, the scale degrees are B, C and D, so we add the C# that falls between C and D. This holds true for the fifth and fourth strings as well. But on the top three strings, where there are five frets between the three scale degrees, we have to choose which of the two possible passing tones to use. I prefer the higher of the two (FIGURE 47).

You can then descend through the pattern in reverse order, but I like to play it in a repeated descending/ascending/descending manner that falls into a meter of 5/4 (FIGURE 48). What I like about this approach is that the picking patterns remain constant, down-up-down-up, as you move from string to string. Practice this in a ascending manner too. I recommend working on these patterns in repeated two-string pairs, or just on a single string (!), before moving to the sequence that carries the pattern across all of the strings.

OTHER SCALE-PLAYING APPROACHES

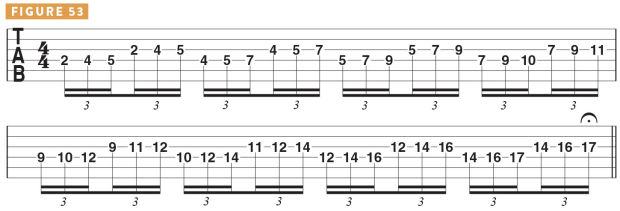

In order to be able to apply everything that we’ve covered to different keys, you need to know where the correct notes fall, where they lay on the fretboard. To me, the best way to get a handle on this is to practice playing scales on a single string. Start on the high E and play all of the notes of E natural minor, also known as the E Aeolian mode: E F# G A B C D (E F# G). This series of notes is the same as the G major scale, with one note that is sharp, F# (FIGURE 49). You could fret each note with the same finger if you like, but I prefer to use a three-finger approach that shifts positions up and down the neck. Then do the same thing on the B string (FIGURE 50), and then all the remaining strings.

As you move three-note shapes up and down the top pair of strings (the B and high E), you realize there are three fingering sequences that repeat, such as index-middle-pinkie (1-2-4), index-ring-pinkie (1-3-4), or index-middle-pinkie with a stretch (or index-ring-pinkie with a stretch, when you are higher up on the fretboard).

You discover that this applies to the scale as played on any string, such as on the A and D strings (FIGURE 51). The next step is to apply these fingering patterns as you move from one string to another, which is exactly what one does when playing solos or song riffs. For example, if I’m sticking to the E natural minor scale while moving between the D and G strings, I can see how these sequences work together. Here’s the scale on these two strings (FIGURE 52). If you play three notes on one string and then three notes on the next before shifting positions, you get a six-note pattern (FIGURE 53).

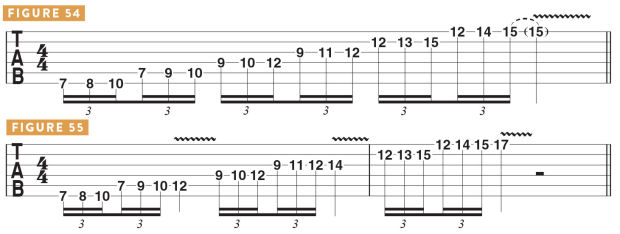

Just as there are three different fingering shapes on one string, there are six different two-string shapes, or sequences, as we move up the D and G strings, and these shapes repeat all over the fretboard. The first is parallel, 1-3-4 on each string. The second is 1-2-4, then 1-2-4 with a stretch. Then 1-3-4 followed by 1-3-4 with a stretch, or 1-2-3 followed by 1-3-4 with a stretch. The fifth shape is 1-2-4 followed by 1-3-4. The sixth is 1-2-4 with a stretch followed by 1-2-4 without a stretch on the higher string. And the seventh shape is a repeat of the third one, 1-3-4 followed by 1-3-4 with a stretch.

If you learn those six patterns, this is all you need to know, as they repeat all over the fretboard, and this is true for all of the diatonic modes. There is a slight shift necessary when moving between the G and B strings because these two strings are tuned a major third apart, not a perfect fourth, like all the other adjacent strings. And remember that these fingering shapes will apply to playing the scale, or any scale, in the more conventional manner—within a single fretboard position across all six strings.

The most powerful way to utilize these fingering concepts is to apply them to patterns that ascend and descend the board, enabling you to cover a lot of ground. You’ll find that the specific shapes will repeat when moving through three octaves, which is something I take advantage of all of the time in my playing. If I start in seventh position on the low E string and play 1-2-4, 1-3-4, I can move up one octave and start on the D string, and the fingering sequence is exactly the same. If we move up one more time to the next higher octave, as played on the B and high E strings, it’s the same shape again (FIGURE 54).

It’s so valuable and important to be aware of how each of these shapes repeats, because if you learn it in one spot, you can move up, and there it is again. Your mind becomes very familiar with how the shapes look and feel, as well as how they sound as patterns played over chords.

These patterns consist of six notes, so we’re leaving out one of the degrees in a typical seven-note scale. If you’d like to include every scale degree, what I do is shift up one scale degree following the sixth note in each sequence. This results in seven-note patterns (FIGURE 55). Now you have a scale pattern that ascends through three octaves, wherein you can simply and easily identify the shapes. This is a great way to move up and down through scale patterns in a seemingly effortless way while also covering a lot of fretboard territory.

Source: www.guitarworld.com